SAN FRANCISCO, California: Sports is a lucrative business, and sports superstars are a testament to that.

The defining quality of a sports superstar is achieving at the highest level of their sport, and normally, making a handsome living off it.

For sports where a nation has a strong tradition of success and the infrastructure for grooming world class athletes, the path to stardom is well-beaten. But what if it isn’t?

In Malaysia, for instance, Lee Chong Wei’s tremendous success in badminton is less of a mystery than Nicol David’s rapid rise in squash.

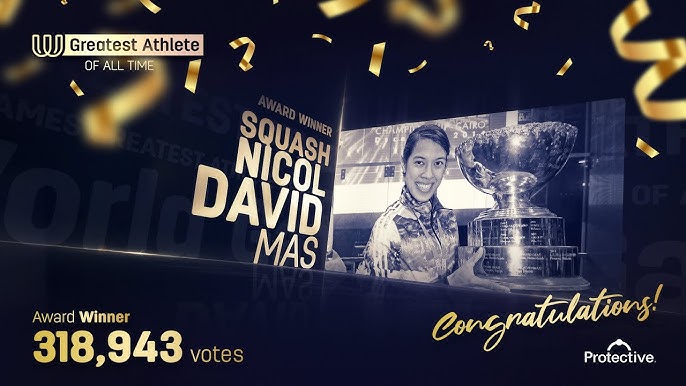

Despite coming from the humble region of Southeast Asia, David was recently crowned the World Games’ Greatest Athlete of All Time. New York Times dubbed her the Serena Williams of squash.

Singapore was an Asian force and top Southeast Asian nation in squash in the 1980s and 1990s, where the Singapore-Malaysia squash rivalry was like a “Causeway Derby”.

David’s superstardom has effectively shattered the glass ceiling for Southeast Asian athletes, but the reality for Singapore squash hopefuls is it’s still a lonely road to the top.

When the Singapore men’s squash team won the 2017 SEA Games gold medal after 22 years, TODAY reported the team had neither adequate facilities to train at nor the proper funding.

The lack of facilities came as no surprise to me as my younger brother had trained as a national junior player with the 2017 team that won gold. But the absence of financial support for talented athletes to pursue such a historical sport in Singapore is perplexing.

What did Malaysia do right? What lessons can be learnt?

NICOL DAVID VS GOLIATH

Unlike the “national sport” of badminton in Malaysia, squash is not an Olympic sport. This status alone ought to have immensely reduced any government funding for squash players in both Malaysia and Singapore alike.

Then came the Kuala Lumpur 1998 Commonwealth Games, where squash made its debut.

The then-14-year-old David did not win any medal, but it was the moment Malaysia came to know of David. A few months later at the Bangkok 1998 Asian Games, David would win the historic gold.

Then something rather unusual happened.

Government funding alone is rarely enough to transform a regionally successful athlete into a globally renowned one. On Mar 1, 2000, at just 16 years old, David landed a worldwide sponsorship deal with Malaysia’s very own Hotel Equatorial.

By 2006, as her career began to take off, CIMB Group backed her with million dollars’ worth of sponsorship. Both local corporate sponsors would become long-term sponsors of David’s illustrious career, which includes being the longest-reigning world number one squash player.

Add the vibrant Malaysian local media machine to this, and a Goliath-slaying superstar is born.

Today, Malaysia has a deep well of squash talent and domestic competition is intense. But two decades ago, as a pioneer, David had to be strategic to stay competitive.

David often credits her relocation to Amsterdam to train with Liz Irving in 2003 as the turning point of her career. This move is not unusual if one’s nation does not have a tradition or the infrastructure for success.

UNLEASHING ‘THE POCKET ROCKETMAN’

UNLEASHING ‘THE POCKET ROCKETMAN’

Take Malaysia’s successful cyclists for example.

When I was producing Azizul Awang’s short documentary just a few years ago, I came to learn of the extraordinary challenges he overcame to win both Malaysia’s and Southeast Asia’s first ever Olympic and World Champion medals in cycling.

Nicknamed “the pocket rocketman” for his relatively small but speedy stature, the lack of track cycling facilities in Malaysia meant Awang and the small Malaysian cycling team had to relocate to Melbourne, Australia, to train under head coach John Beasley in 2007.

“He’s small, he doesn’t produce a lot of power, he would fall through every crack in the system”, said Beasley who also revealed that Awang had “no money” and faced language barriers when he first arrived in Australia.

Despite it all, Awang and Mohd Rizal Tisin would bag historical World Championships medals in 2009.

And in the same year, Malaysia’s largest trading conglomerate Sime Darby would begin a historic three-year sponsorship deal of RM2 million (US$485,000) for the 2012 Olympic-bound cyclists.

Remarkably, a potentially career-ending accident in 2011 and a failed Olympic medal bid in 2012 did not keep Sime Darby away from pouring in another RM2.85 million into Azizul Awang and Fatehah Mustapa in 2013 to fund their quest to win an Olympic medal at Rio 2016.

Not only did Awang finally pick up the long-awaited Olympic medal in 2016, he followed up in 2017 to make history again with a World Champion title to Malaysia’s name.

CIMB and AirAsia have since come alongside the father of two as major sponsors while Sime Darby pledged RM2.6 million to sponsor the next generation of young Malaysian cyclists.

Like in squash, Singapore cyclists have also struck SEA Games gold medals in recent years: Calvin Sim (track) in 2017 and Dinah Chan (road) in 2013. Both tremendous results from a nation without proper training facilities like a velodrome, not yet at least.

Both Sim and Chan had to leave their full-time jobs temporarily in order to pursue their sporting careers. Each had received some form of government funding or scholarship.

Yet as the journeys of Malaysia’s Nicol David and Azizul Awang would illustrate, to shatter the regional glass ceiling in sports where Southeast Asians are the underdogs, it will take a village.

THE ‘KAMPUNG SPIRT’ LIVES ON

With limited government funding, the private sector in Malaysia stepped in.

Even when the private sector fall short, sheer grit and public funding sometimes can plug the financial gap. That was how Malaysia’s first Olympic figure skater, Julian Yee, who in 2016 turned to crowdfunding in his bid to become the first Malaysian to qualify for the Winter Olympic Games at PyeongChang 2018 – and he did.

Malaysians pulled through for the 2017 SEA Games champion, as he raised close to US$17,000 on his crowdfunding platform in his successful pursuit of his wild Winter Olympics dream.

Though Yee did not win an Olympic medal, his successful Olympic qualification with financial support that came through “kampung spirit” makes his history-making story not quite different from Nicol David’s or Azizul Awang’s.

Rinong shocked Malaysia and the world when at 19 years old, she became the first Malaysian female athlete to win an individual Olympic bronze medal at London 2012, and then a silver at Rio 2016 in the synchronised 10m platform event with Cheong Jun Hoong.

The media darling was then invited to grace the cover of glamour magazine Tatler Malaysia, in a high fashion shoot that cemented her as a true sports superstar.

Rinong’s 2012 trailblazing was a major springboard for Malaysia’s crop of diving talent. Malaysian divers have won medals at every World Championships since 2013 and is today the second most successful Asian nation at the event with China taking the top spot.

In 2017, Cheong Jun Hoong also picked up Malaysia’s first ever diving World Champion title.

Like squash, diving only became a known sport to Malaysians at the Kuala Lumpur 1998 Commonwealth Games. Unlike squash and cycling, however, diving has not drawn much private sector support.

Malaysian divers, who were led by Chinese coach Yang Zhuliang from 2008 to 2017, had to commute to China to train in proper facilities.

Diving is after all a sport dominated by China, Russia and America. This keeps Malaysian divers grounded in their studies, while juggling their sporting dreams.

Besides two Olympic medals, in 2018, Rinong graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Sports Science Management funded by the Universiti Malaya Olympian Sports Scholarship she had received after London 2012.

Rinong was the inaugural recipient of the scholarship, which covers tuition and accommodation as well as welfare and training allowances worth RM30,000 a year. By 2017, the scholarship was extended to 7 other Olympians, three of whom including Rinong are divers.

From squash to cycling to diving, these are sports where Malaysians had lacked local training facilities and were once written off at the global sporting stage.

Yet, Malaysian athletes collectively turned the narratives around one sport at a time.

The Olympic medals, world titles, superstardom, and for Negaraku to be heard by the world at the biggest sporting events – all that were once unthinkable, but not anymore.

Source: CNA/el

UNLEASHING ‘THE POCKET ROCKETMAN’

UNLEASHING ‘THE POCKET ROCKETMAN’